The new issue of School Library Journal features a cover story called, “Next Year’s Model: Sarah Ludwig left the library, became a tech coordinator, and forged a path to the future.” Unless I have misinterpreted the article, author Linda Braun wonders if school librarians have to leave the library and take on a completely different job title to do the work of a modern school librarian. The thesis seems to be that school librarians taking on job titles other than school librarian, like “technology coordinator”, might be the future of the profession. While I’ve had my own misgivings about the future of the profession, I respectfully disagree with Linda Braun and would argue that such a path will only lead to the demise, not the flowering, of our profession’s future.

In the last year, I’ve had conversations with colleagues like Ernie Cox, Kristin Fontichiaro, Heather Braum, Jennifer LaGarde, Susan Grigsby, Beth Friese, Linda Martin, Peter Bromberg, Melissa Johnston, Diane Cordell, and Sara Kelley-Mudie about the future of school librarianship. We’ve wondered about the future of the profession and the challenges of becoming more immersed as an instructional leader and pedagogy specialist in a current model of school librarianship that is physically limiting in the sense that one person, two at best in most places, is expected to excel in multiple roles for student populations that might vary from 850 to 2500 students and up to 100+ faculty in a building; in some cases, school librarians are being asked to be a teacher, program administrator, information specialist, leader, and instructional partner with no planning period and no clerical assistance. Like Braun, we’ve dared to wonder if we would be better positioned to accomplish the kind of change we envision in our learning ecosystems in another role, perhaps back in the classroom or some other educational role; at times, it’s felt rather blasphemous to even articulate such wonderings. However, I think such questioning and the interrogation of our beliefs, of what we’ve held sacred both personally and as a profession, are healthy so that we can reflect thoughtfully on what we value. Through these conversations I’ve had with my friends, the mucking around in what I believe has pushed me to the edges, particularly as I’ve dealt with some very trying circumstances in the last year that have threatened to encroach upon the heart of The Unquiet Library—the integrity of the instructional services and participatory model of learning I’ve tried to provide my school. The crucibles that I’ve faced personally and as a part of the larger profession have forced me to think long and hard about what I believe and how I might act upon those beliefs.

For me personally, these wonderings have intensified in the last two years as I’ve become much more immersed in my role as an instructional partner and have felt stifled by staffing decisions made at the district and building level and the larger cultural learning climate that like many places, emphasizes outcomes of standardized testing. At times, I’ve felt very disconnected from other conversations in “library land” that feel removed from my struggle to implement a vision of librarianship that has been participatory and learning focused for the last six years, a vision that I’ve tried to transparently share through this blog, presentations, published articles, webinars, and my library’s online presence, including my multimedia monthly and annual reports and research guides, I’ve been hopeful that sharing the work that I’ve done through my library program with students and teachers has shown a glimpse of what IS possible through school libraries.

However, to scale out what I’ve been with both depth and breadth and to leverage more impact in my learning community, I need additional librarians (and have the numbers to justify it) on my staff—it is simply not physically possible to reach 1800 students and 100 teachers under current conditions because the bottom line is that cultivating true partnerships for learning is extremely time intensive in terms of planning and actual implementation. Participating as a co-partner in the instructional design process, which is essential for creating meaningful, rich learning experiences, and participating in all phases of the learning experiences, including formative and summative assessments, requires a tremendous amount of care, energy, and time commitment. Nurturing and tending to these relationships require constant care much like a garden—you can’t plant the seeds and then just assume they will grow with minimum care or attention. And while technology integration is a part of these processes, it is not THE focal point—I’m more concerned with high quality instructional design and teaching than I am technology integration–if we don’t have sound pedagogy that we’re collaboratively crafting with teachers and students, we’re not really getting to the core of what libraries should be about—learning. With more human resources, we could reach more students and teachers not just in the physical and virtual learning spaces, but more importantly, to have the time to cultivate relationships and trust with our teachers, the true cornerstones of building communities for learning and partnerships for learning.

There is no doubt the current model of school librarianship is way past broken–this is not a big secret. It’s an outrageous, outdated model that basically demands we be the equivalent of a martyr and ultimately sets us up to fail in the kind of excellent and instructionally oriented work modern school librarians strive to achieve. It’s a model that has left us emotionally, physically, and intellectually drained and beaten up, a model that has failed to evolve with our mission and philosophy of 21st century librarianship. Instead of expecting less, we should be expecting more in terms of a model that would be supportive of the work we’re trying to do. And while I appreciate conversations about our future and how we shape that as school librarians, I respectfully disagree with Linda Braun that the future of school librarianship is to walk away from our title and to try and do the same or similar work under a different title. While I wholeheartedly applaud Sarah’s work, I’m disappointed Linda Braun did not include any discussion of school librarians who are doing the same work and possibly more in the role of school librarian. Yes, the term librarian is ridiculously laden with an array of complex political, cultural, and historical dialogic voices. But I think when we look at the short and long-term future of school librarianship, a conversation about elevating our role as instructional leaders and learning mentors would be a more thoughtful conversation. To imply that we as school librarians can’t do the work Sarah (whom for the record, I count as a valued friend and colleague, and whose work I very much respect) is doing and more with the title school librarians marginalizes the revolutionary work that many of us are doing (and under trying conditions, I might add) in the trenches of our nation’s public and private schools.

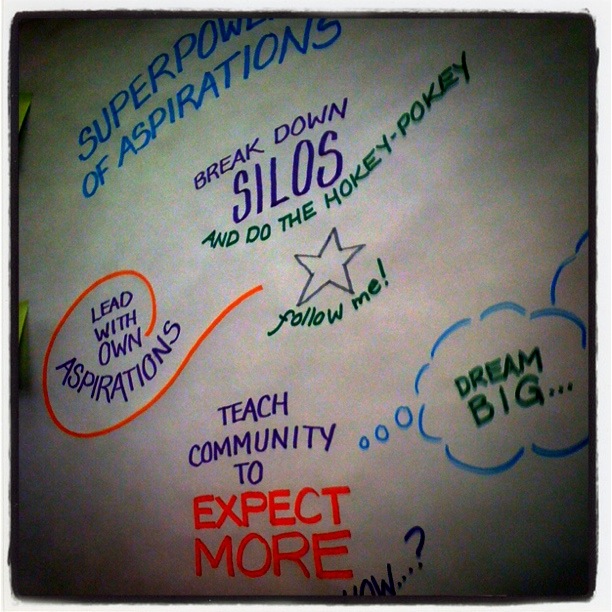

Rather than suggesting we can’t do the kind of work we know matters under the name “school librarians”, I would suggest we need to boldly embrace the term librarian and dispel the old stereotypes through more widespread and fearless sharing and transparency in that work that keeps students and learning through multiple formats at the center of what we do. Our challenge is how do we grow school library programs in these difficult economic times and a shifting educational landscape that is increasingly discounting the value of school libraries as an essential partner in learning spaces? How do we encourage our learning communities to expect more, not less of us, and to support a model of school librarianship that would increase not only the quantity of school librarians, but the quality of school librarianship as well? I still don’t believe it is through mandates, but instead, we must find better and more effective ways of engaging school and district administrators, school board members, teachers, students, and parents in honest conversations about librarians as instructional partners. How do we engage them with the shared story of library we’re trying to compose and construct with our teachers and students?

I do not have all the answers, and I’m wrestling with these questions as I and The Unquiet Library program face our most severe crucibles yet. And while I have had my share of dark days full of doubt and questioning, in my heart I still believe in the possibilities of libraries and school librarians–but those will never come to fruition if we acquiesce and abandon the effort to elevate the library as a site of participatory culture and a cornerstone of every child’s learning experience in schools, as a partner who can support our teachers by being embedded as part of the team to give every child positive, constructive, and meaningful learning experiences. Changing the perceptions about what modern school librarians do, not our job title, is essential for the future of this profession. Finger pointing and the blame game are ultimately counterproductive at this juncture in the profession—we cannot change what has happened in the past, but we CAN make a difference for the future with the work we do now if we will carry the banner for school librarian more assertively and with respect for the possibilities that are inherent in that name: a librarian is not a technology specialist, but instead, a learning specialist and architect.

While I love my physical library space, that is not what I’m trying distribute throughout my building, but instead, it’s the experience of library and myself, the human resource and all the energy, expertise in many kinds of literacies, and desire to help students learn, that provides the most benefits to my school. I wholeheartedly applaud Dr. David Lankes and his assertion that, “… great school librarians have collections of lessons they teach, student teams that assist teachers with technology, and collections of good pedagogy. Want to save money in a school? Close the library and hire more school librarians.” As long as I have a space to teach in the building and the means to teach teachers and students, I can bring the experience of library anywhere. Great and talented librarians, contrary to what those making budget decisions might think, are not easily replaced and whose absence won’t be appreciated until it is too late for our students and teachers.

We are librarians. Own it. You must believe even when others do not. For every doubter, hater, or naysayer, there are children and teachers whose lives and classrooms a school librarian has impacted for the good, and there is no longer room for those who do not put community, service, and people first. Let us not shrink from what that means and what it can mean, but instead, strive to grow the successful models of school librarianship that DO exist and DO make a real difference because they have a librarian whose work, struggles, passion, and collaborative efforts with teachers and students do matter in helping students compose their own narratives of learning.

I agree very much about embracing, owning, and redefining the word “librarian.” “School media specialist,” “cybrarian,” etc. imply that librarians were not always on the cutting edge of information technologies, which most of them always were. It’s endorsing the view of librarians as out-of-touch, and, in some ways, disrespecting other librarians, (i.e. You’re an old fuddy-duddy, but I’M a cybrarian!)

I have always called myself a librarian. We can educate students, colleagues and the public in the crucial role that librarians play in print and digital culture, critical thinking, information literacies, etc., without resorting to cutesiness or betrayal.

LikeLike

Hi Julie. I think the difference here is that when this article was written, I was *not* a librarian by title. I have always called myself a librarian when people ask me what I do, because it’s my profession–but it’s literally not my title. When I took my job as Academic Technology Coordinator, I certainly didn’t do it to imply that librarians are out of touch….I just took it because I thought the job sounded really cool. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you! I never got why we had to be called Media Specialists or Technology Coordinators to be taken seriously. People need to get over this Marion the Librarian stereotype and see that librarians can do it all–without the fancy title. (Except Garrison Keillor, whose “Ruth Harrison, Reference Librarian” skits are hilarious!)

LikeLike

I think I’ve been able to function more fully as a librarian in my retirement: no physical library to anchor me, few time constraints, free to embed myself in social networks, available for f2f interactions (visiting a photography class, helping with a local “battle of the books”). I DO believe in our profession, but I also believe that it must continue to evolve.

LikeLike

WE HAVE TO evolve, to be able to disseminate information in a fashion that is on par with the technology that is prevalent in society.

LikeLike

Thanks to strong progressive teacher-librarians from the past and from our current staffing, we have tried hard to develop and secure instructional services and nurture participation and collaboration for my large (1800 gr10-12) high school. We have become a valid vibrant learning commons that students, teachers and admin all support but we have a culture to build on that made the library program important. We have 1.6 TL and 1.0 Clerical and ongoing budgeting and engagement but the landscape of the school library is changing so fast we cannot keep pace. Policy, pedagogy , demographics and much more have changed beyond our ability to lead. We do our best and we are strong but change outstrips our abilities and energies. Therefore, when I read in SLJ the role as technology coordinator I rather snickered with cynical zest because that is a role I have evolved into from the start. We are the technology, information AND pedagogy hub. That said, we are given less influence and participation in the policy making and decision-making than we once had. As the demands and needs changed we responded but now the system is too fast and too top heavy to truly DESIGN process or practice. We have become a digital triage center. The irony is that our community still SEES us as a content place. We have not reduced or slashed any sector of our school library anatomy but rather have tried to cope by adding on more limbs and bionic parts. Like HAL we may be losing our sanity. thanks BJH, Al Smith @literateowl

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Things I grab, motley collection .

LikeLike

I’d say we agree on quite a bit, particularly on the importance of students receiving the best possible support and opportunities from their schools and teachers. If school librarianship is broken let’s work together to fix it. The important thing is for students to gain the skills that they need and that’s what’s happening at Hamden Hall where Sarah works. They are lucky to have someone that can embed library and information skills with technology skills so seamlessly.

LikeLike

I’d say we agree on quite a bit, particularly on the importance of students receiving the best possible support and opportunities from their schools and teachers. If school librarianship is broken lets work together to fix it. The important thing is for students to gain the skills that they need and that’s what’s happening at Hamden Hall where Sarah works. They are lucky to have someone that can embed library and information skills with technology skills so seamlessly.

LikeLike

Linda, I think where we differ is that your cover story on SLJ offered leaving the role of school librarian as the “next model” of school librarianship in order to effectively do the work of school librarian. That is very different from what I’m stating in my post here. What’s really troubling to me is that nowhere in the article do you address why the school’s current librarians are not doing what Sarah does as “academic technology coordinator” or why her administrators didn’t hire here as librarian to do what she is doing now. What is even more baffling to me is why the school’s librarians are completely absent from even some of the most basic tasks Sarah identified like helping teachers set up blogs or teaching a citation management tool like NoodleTools. It’s as if the school’s librarians are invisible in that building—why does the admin think so little of them and not expect more? And if they weren’t stepping up, why not fire them and put Sarah in that role? Many of us who are school librarians by name have been indeed expected more and publicly shared through many avenues of how we’re doing just that.

While I absolutely respect Sarah and the work she is doing, I don’t see that she is accomplishing any more than many school librarians I know; I could give you a long list of school librarians who are doing exactly what Sarah is doing as “school librarians” and with no disrespect to Sarah, there are many who have been and who are doing even more than what was described in the article. In addition, the article implies that what she is doing is the exception, not the rule, in America’s school libraries, and I vehemently beg to differ. Frankly, I was offended by the article and felt it completely ignored and dismissed the amazing work so many school librarians are doing and have generously shared through their blogs over the last few years. When a publication that is supposed to be one of your profession’s flagship publications puts an article like this one front and center as its lead cover story and touts a school librarian taking on the same work under a different title is a viable option to fixing the broken model, readers can’t help but ask, “Then what is the profession of school librarianship supposed to be doing?” Your perspective is quite opposite from the model I envision–I’m talking about growing it, and you’re talking about people who aren’t school librarians doing work that is identical to ours and reducing us to something other than the five roles identified by AASL. How is forsaking your job title as school librarian and doing the exact same work under a different title the future of THIS profession?

The other issue I have with this article is that it represents a very narrow privileged white upper class perspective in focusing only on one Northeastern private school—if we were to examine “next year’s model” more broadly, I think an article that was more inclusive of many kinds of librarians doing innovative work in more culturally and socioeconomically diverse schools and in a variety of settings, including urban and rural public schools, would have given readers a richer perspective.

Respectfully, Buffy

LikeLike

Buffy, while I appreciate this debate and have been reading it with great interest, I must take issue with your suggestion that my friends and colleagues in the library should have been fired. I work closely with the lower school librarian and we are in a transitional period. The library is under new leadership, and we are working to align the technology and library curricula. This is a developing program that we all feel very proud of. In addition, I am fully aware that there are school librarians who are more accomplished than I am. I never meant to suggest otherwise.

I am also troubled by your statements about my school. Unless you know the makeup of the student body, the amount of financial aid we award, and the school’s operating budget, I’m afraid you can’t speak with authority about our situation, just like I can’t speak with authority about yours. It is a common argument to assume that independent schools are wealthy. While it’s true that we have smaller classes than most public schools, we have to make difficult choices just like the rest of the country.

I am not going to address the rest of your comments because I don’t think we are going to see eye to eye, but I felt compelled to defend my school and my fellow librarians, who I care for and respect a great deal.

LikeLike

Sarah:

As I tried to convey in my earlier comments and original post (plus our discussion thread via FB yesterday), I respect and applaud the work you are doing; in no way have I intended for my criticism of the article to be a personal or professional criticism of you; additionally, my thoughts are not intended to criticize your school or colleagues.

While I’m happy to hear that the library program itself is evolving, I still have to ask why were they not providing these services you are doing now? As you pointed out, we as readers are not privvy to all of those details because they were not fully fleshed out in the article—it would have been helpful, though, if Linda had more fully articulated what had been happening with the library program previously and the impetus for change now. To me, their absence was glaring in that article. The fact that you were not hired to be an actual librarian and instead were hired under a different job title to do what many school librarians have been doing for some time now implied that the current library staff had not taken ownership of those roles outlined for AASL—sometimes when that is the case, it may be because of severe restrictions created by admin (which in that case, that begs the question why they would only want librarians to do the traditional tasks of yesteryear); in other cases, though, it’s because librarians have not evolved and kept up to fully embody the five roles put forth by AASL (and as sad as I am to say it, we know there are still librarians like that in public and private schools). I appreciate and respect your defense of your colleagues and in no way mean to attack them, but I do think it is legitimate to ask why they weren’t already doing what you are doing in your current role, especially if you consider them to be more accomplished colleagues.

You are absolutely right that every student population and community is different within both private and public schools. Again, my comments were not meant to criticize your school or your colleagues, but this article focused on a school environment that does not represent the experience of most school librarians who are in public schools. Again, if the cover story had not portrayed this as “the next future” of the profession, then perhaps it might not be a point of contention for me. However, private schools are not bound by many of the crippling federal and state mandates as public schools. This is not to say there are not your own unique set of challenges—everyone has them. However, I still stand by earlier assertion that an article that was more inclusive of many types of school librarians doing innovative work to point to as where we want to be who are in differing socioeconomic, cultural, and school environments, would have provided a much more well-rounded picture of the successes and challenges professional school librarians are facing. I think in general, many of our school library publications and conferences have failed to address diversity issues, and I would like to see more conversation about those challenges and solutions in many different settings.

I also appreciate your taking time to comment here in such a thoughtful way. We both come from very different backgrounds and experiences, and while we may not agree on all points, I’m glad we can engage in a respectful dialogue about these issues.

Respectfully,

Buffy

LikeLike

I’ve been thinking a lot about my response to the article and this discussion. Perhaps SLJ set Sarah up somewhat by choosing the headline they did, or running this as a cover story rather than as a feature. I certainly don’t fault Sarah for taking this job opportunity, for sharing her story, or for trying to understand for herself how this would work, or how transparently she shared her learning process. I certainly didn’t feel like she implied at any time int he article that what she was doing was different than or better than what other librarians are doing or have done. Perhaps I took the article a little differently. I find it interesting to understand the many ways those of us who are librarians work in all our various schools. In fact, part of what I enjoyed about the Computers in Libraries conference was seeing the myriad of ways librarians work with students or public patrons or teens in different settings. When I read this article, I considered it one example of that. On the other hand, I totally understand the implications that SLJ made by positioning the article the way it did(implications, that , I might add I feel were unintended, because we certainly know how much SLJ has included articles about and pondered along with us about the future of school librarianship and provided many examples of that in its pages. ) And frankly I think the article reflects a little of the confusion I face in my own school–I feel I am often a hybrid librarian/techie and while I embrace my role as a librarian, I also often find myself with one foot in an instructional technologist role as part of my work with teachers, so I relate to the bleedover of roles. In fact, in my own district, the librarians wrote up the job description for the first instructional technologist our district hired, and in fact, the first person they hired happened to be a librarian. (I often think of that when later on we were denied access to things from the very people whose job description we wrote, but that’s another story.) And frankly, I don’t think the diversity of our schools, or public/private really affects the challenges we all face in trying to figure out the changes occurring in our profession. We all face challenges and we are all trying to best serve the students and school in which we serve. I also have concerns about throwing colleagues under the bus when we don’t know their situation. But that is part of an ongoing debate I see in education in general–how we deal with educators who are slow to change or embrace new tools and methodologies. I for one think that we need to seek out their strengths and nurture them along because change is a slow process and just because people are slow to change doesn’t mean they don’t have skills to offer. (Anyway, I’ve seen the same debate in the tech listservs I belong to, on blogs about teachers, etc.–it’s not just a debate we as librarians are having. ) But I agree that however we approach change, we have a lot of work to do with colleagues, administrators, colleges of education, library and information science programs, teachers, and more. I agree that we are understaffed and despite the tremendous amount of work many of us do to be transparent, to model being instructional leaders, to share what we do, that the importance of what we do is often minimized or disregarded or misunderstood. We have a lot of work to do. I feel passionately that it is important. But I also want us to also embrace curiosity at all the ways we do try to figure this out.

LikeLike

Carolyn:

Thank you so much for taking time to share your reflections—I always respect the thoughtful and conciliatory approach you always take on controversial issues. I also hope you did not interpret my post as a critique of Sarah–as I’ve stated several times now, my issue is not with her, but with the thesis of the article by Linda Braun and the implications of that for our profession.

I thought a lot about your comments during this morning’s run, and just a few reflections here I’d like to share:

1. Re: throwing colleagues under the bus. I’m all for helping others if they are taking action steps and initiative to improve. At the same time, don’t our children deserve the very best to help provide their education? Would you want your child to be someone’s classroom or library who was less than stellar? Would you be willing to see a doctor or other professional who had good intentions but wasn’t quite up to par? I’m sorry, but I think there is something very wrong when we allow people who either no longer care or who are not talented educators to keep their jobs. Case in point: a colleague in mine lost her position as a high school librarian when the district made reductions in staffing. Even though she was regarded by her principal and faculty as a talented and passionate librarian, the district cut her based on seniority in the district. The person who replaced her sat in the office for most of the next year, and children and teachers were not served. Why was this tolerated and accepted?

I don’t know the librarians in Sarah’s school, and I would have liked to have heard more from them and/or about them in the article—perhaps that was a major flaw in SLJ’s editorial process. However, I don’t think it is throwing anyone under the bus to ask the question, if they were respected and considered major contributors to the learning process in that school, why didn’t the school admin hire Sarah as a librarian and add her to their department? If there is a valid reason for that, I would love to know and for us to learn more about what the librarians who are in the building do. I just fail to see why Sarah was not placed as part of library staff and why the article is framed as she had to leave the library to do the work of a librarian. As you pointed out, perhaps this is a major failure in semantics in the composition and editing of the article.

2. Like you, I love attending conferences like Computers in Libraries and Internet Librarian. I am friends with a lot of different kinds of librarians in different spaces—I am all for busting out of silos. However, look at the list of speakers at this year’s CIL 2012–with the exception of vendors and directors, nearly every person listed is identified as some kind of LIBRARIAN. Not a facilitator, not a coordinator, but a librarian. Yes, they may work in a variety of settings, but they are part of library staff and identified as librarians. In this article, Sarah is not. Why are we as school librarians so apologetic for the term and willing to give up the title that is part of our larger profession?

3. You stated, “And frankly, I don’t think the diversity of our schools, or public/private really affects the challenges we all face in trying to figure out the changes occurring in our profession. We all face challenges and we are all trying to best serve the students and school in which we serve.”

I could write an entire blog post on this, and I just may, but to say that the dynamics of power and the discourse about our profession and practices are not informed (whether we realize it or not) by race, class, and gender is naive and misinformed. Perhaps my background in critical theory from my graduate school days at UGA influence my perspective, but school is one of our major cultural institutions where race, class, and gender have and continue to shape our work—I think being aware of that, our own biases, and trying to be cognizant of how that impacts our work is absolutely imperative. To say that our work happens in a vacuum and that diversity isn’t really a factor—I respectfully but passionately disagree with you on this point.

I appreciate the multitude of honest perspectives that you and others have shared in this space and hope we can continue the conversation in ways that will allow us to share our opinions and as you said, “pursue curiosity” in a thoughtful and respectful way that will help us all push our thinking and to better the profession.

Respectfully,

Buffy

LikeLike

Indeed your summary speaks true. thanks

LikeLike

Perhaps I wasn’t entirely clear, but I don’t particularly appreciate the implication that I am naive or uninformed as I certainly realize that the diversity of our schools and public/private sector has an impact on what we do and shapes that. But I also believe there are also universals that we do all face, and there are also many different types of diversity . What I was attempting to convey was that I felt diversity was outside the scope of what this particular article was about. — an article about Sarah serving as an instructional technologist and whether or not that was the future of librarianship.. Her comments about challenges of collaborating with teachers, introducing new technologies, or working with students seem similar to ones many of us face, no matter what sort of position.(And one area of commonality that I think my own instructional technologists share with us as librarians). And to reiterate, I also hesitate to criticize the librarians at her school since there was very little information about them in the interview so I would have nothing to base that on. Without that information, it seems a little presumptuous to make a determination that they aren’t being successful and possibly hurtful to the librarians involved who we know nothing about. Also, in my reading of the article, it didn’t appear that the school was attempting to hire another librarian but that Sarah saw a posting for a technology position and applied, and they hired her. If I misread that then my apologies. Overall, sadly I feel for Sarah, who must have been thrilled to find herself on the cover of School Library Journal and to share her experience as any of us would have. Perhaps it was a misfire on SLJ’s part, and perhaps there were things excluded from the interview that might have been helpful to know about. I don’t disagree that embracing this situation as a model for new librarianship was a misfire. I just feel uncomfortable making presumptions not having all the information at hand.

LikeLike

I wonder if part of the issue for Hamden Hall is the same issue I face at the upscale, private CT school where I worked. While the school thought of itself as progressive–and they were certainly socially progressive–pedagogically they were very conservative. More specifically, they had a very conservative view of what the library should be.

When I arrived, they hadn’t had an LMS for two years, and the library was nonfunctional. I actually overheard a teacher telling a student, “Don’t bother using the school library. They don’t have anything useful.” Students avoided the place.

My first job was to make the space more inviting. I brought in cushions, posters on the walls, and created collaborative space. I worked to establish myself as the go-to person for collaborative ideas, technology issues, and research instruction. My principal agreed with all of this in theory, but found the actuality more distressing. The cushions and posters had to go (kids lounging on the floor with their iPods looked “sloppy”), the talking in the library, which I thought was reasonable, was too distracting and we had to enforce a silence policy.

Moreover, once I decided to move on, the person my principal most wanted to hire made it clear she wasn’t interested in teaching or technology, and her first goal would be to build the fiction collection.

While there are certainly private schools who have “the vision,” I suspect they’re the exception rather than the rule, and many East Coast private schools, especially the older ones, want that green lamp-shaded library image. I suspect the librarians at Hamden Hall had some unspoken pressure from above to conform to that.

Or I could be completely talking out of my hat.

LikeLike

Thanks for this post, Buffy. A year ago I was called into an office by my school administrators where they told me that they no longer needed a librarian. They said their PreK through 12th grade school could exist perfectly well with no school librarians because they were going to hire a technology coordinator. I tried explaining to them that every duty they described in the tech coordinator’s job posting was exactly what I had been doing before they chained me to me desk with eight study halls a day. They seemed shocked that a LIBRARIAN could teach classes or that I would even want to. My fellow teachers raised an uproar at the news I would be leaving and bombarded the admins with stories of the many times I helped plan their lessons, teach their classes, and improve their culminating projects. It didn’t help, though. They couldn’t get their mind around it. A librarian to them was just someone sitting in a room with books. I agree with Buffy. We shouldn’t have to change our names and masquerade as someone/something else, we just need the world to understand what a librarian actually does. What we do and what we stand for.

LikeLike

I think that SLJ should feature a “counterpoint” article and let Buffy showcase the work of our professional colleagues who still brand themselves librarians. Technology encompasses more than a facility with online tools; information skills AND literary appreciation are, or should be, our dual concerns.

LikeLike

I have been teaching for years in my library. Haven’t you all? (Thank you Buffy for that wonderful networked student program I picked up from your blog. You are the best!) I also do ordering, inventory, weeding, that sort of thing as I learn to pin, blog, make Delicious accounts. (I was on their main page for weeks after I made stacks to show the students how to do it; my students were impressed!) I even have the school archives and children come back to visit with potential spouses to show them the old yearbooks and newspapers. We have over the years been the film club, had our own academy awards and have sent students off with those dreams and skills. One lately worked with Robin Williams, another is starring in a new fox series. For research, we have our own little program that really is just the most old-fashioned set of steps for our middle schoolers that you can imagine. It works. You know, note cards! Yep. For Kindergarten, how about puppets? Or one-on-one take their hands and walk with them around the stacks. In the end, I don’t know what I believe about all the changes. When hasn’t it been that way? Don’t you think? I like the idea of having a bag of tricks. Why throw anything out? You never know when you will need it. I can photoshop and I can color. I use an ipad and books. I love change; I love permanence. I love saying I am a librarian, keeper of the secrets in the books and databases.

LikeLike

Lorna, beautifully and eloquently stated. Thank you so much!

LikeLike

I find myself in a similar position to 4sarad. As budgets became tighter, my district asked me to take on other duties (i.e., supervise study halls in the library, teach three different ESOL classes) that not only tied me to the physical location of the library, but took away my ability to do the real job of a librarian. I don’t have the time, space, or freedom to truly collaborate with my colleagues. I have so many great ideas, but no way to execute. Now, my position has been eliminated at the end of the school year. I was unable to say no to the additional responsibilities, but I would agree that I’m no longer an effective librarian.

LikeLike

When I read the SLJ article, I was also concerned about Sarah’s change of title and the fact that her job is exactly what I have been training to do. As a LMS grad student at Pratt Institute, I have observed fantastic school librarians in urban public and private schools. The reason they are fantastic is because of their emphasis on collaboration and cultivating information literacy in both students and teachers, not for their abilities to organize and catalog books. As Buffy says about Sarah Ludwig, “the article implies that what she is doing is the exception, not the rule, in America’s school libraries.” If her role as instructional partner is the exception, why am I learning how to teach research classes and integrate resources and technology into my future school’s pedagogy? If I am expected to monitor the library’s circulation desk at all times, I certainly signed up for the wrong profession. I switched to school librarianship from teaching English because of the vast potential of our field, the potential for change. I wanted to be part of that stereotype shift and help forge the path to the future. When my friends and family ask why I want to be a librarian, my answer is to encourage and teach lifelong learning, because I find real-world skills lacking in most traditional classrooms. Our digital world is all about connectivism and collective knowledge. School librarians have the tools and the instructional strategies to show students how to harness the power of information for their own learning; the tech coordinator label detracts from those essential principles, focusing on the medium rather than the message of what students should be learning.

LikeLike

Buffy, I totally agree with you that we need to expand and change the role of school librarian. I love technology but think the assessment, curriculum and leadership pieces are where we will make the biggest impact. Your standards are high, and your work inspires me. Thank you for being a leader in the field, posting your work and advocating for the job of school librarian.

LikeLike

Wow.

LikeLike

It is this passage Buffy wrote that has been in my head since yesterday –

“There is no doubt the current model of school librarianship is way past broken–this is not a big secret. It’s an outrageous, outdated model that basically demands we be the equivalent of a martyr and ultimately sets us up to fail in the kind of excellent and instructionally oriented work modern school librarians strive to achieve. It’s a model that has left us emotionally, physically, and intellectually drained and beaten up, a model that has failed to evolve with our mission and philosophy of 21st century librarianship. Instead of expecting less, we should be expecting more in terms of a model that would be supportive of the work we’re trying to do.”

Yes, yes, yes. This is exactly how I feel. After 35 years, I find myself working harder every year and stretched further and further every year. Not that I don’t love it – but I am exhausted and I don’t see it improving any day soon.

LikeLike

Thank you for sticking up for our profession. Shame on SLJ for this irresponsible slant.

LikeLike

“It’s as if the school’s librarians are invisible in that building—why does the admin think so little of them and not expect more? And if they weren’t stepping up, why not fire them and put Sarah in that role?”

“The other issue I have with this article is that it represents a very narrow privileged white upper class perspective in focusing only on one Northeastern private school”

First of all, as an administrator of the school and Sarah’s boss, I am completely flabbergasted by your comments. How dare you speculate about the school’s internal decisions without knowing anything about the situation? Isn’t that what we are trying to teach our students NOT to do? Especially librarians… Aren’t we supposed to gather all the facts before making a judgement?

Secondly, you have no idea how diverse our community is and you have no idea how much financial aid we award.

I am the person who hired Sarah in her current role as Academic Technology Coordinator. Sarah’s experience and expertise as a librarian is what set her apart from the many candidates we had for the position. Our school has made the strategic decision, as many others have, to merge the technology and library departments because their missions were so aligned and it seemed to be the best way for OUR school to provide the support and strength to the curriculum that we needed. It has truly made a difference in our community, not because we had incompetent librarians who have not been doing their job, but because by aligning these two departments, it put all of our amazing resources under one umbrella. And acting as one department, we are constantly in communication about goals, skills and objectives, always keeping pedagogy at the forefront of what we do. Our teachers find the structure to be so much more effective for their students and for them as educators.

While you spent the entire day yesterday criticizing my colleague and judging my school, Sarah was working with three sixth grade classes, a kindergarten class, attending a planning meeting on using Google Sketchup for upcoming Middle School Earth Summit project, collaborating with colleagues about new initiatives and helping students use new video editing software for a book trailer project.

If you are ever in Connecticut, we would love to have you visit so that you can see, first hand, the opportunities that our current structure provides.

Check out the blog post that I wrote about Sarah at the end of last year… it might give you a glimpse of what she has brought to our community. http://lorricarroll.wordpress.com/2011/06/03/sarah_ludwig-makes-me-smarter/

Lorri Carroll

Director of Technology and Information Services

Hamden Hall Country Day School

LikeLike

Dear Ms. Carroll:

I appreciate your taking time to share your reactions to my blog post and your passionate defense of Sarah, your decisions, and your school. In response, I’d like to point out a few observations:

1. You may not realize that I have known her for over two years and even presented on a panel with her in the past at ALA. I am familiar with her work as a public librarian as well as the last year; she is a well liked and respected colleague not only by me, but by many in public and school library circles. While we may not be on the same page about this particular issue, we do share similar views on other issues in librarianship. No one is questioning her ability, her character, or talent; in no way was my post intended as an insult to her, and I’m truly sorry if you construed my comments as anything demeaning to Sarah (and to Sarah as well). It’s also worth noting that I actually corresponded with her on Facebook about the article prior to writing my post.

If you go back and reread closely, the blog post is NOT a critique of Sarah. The blog post is questioning why technology integration is something that is done in this school by someone who is not considered a school librarian. The blog post was a critique of the article and of SLJ portraying the future of librarianship as librarians having to leave the role and title of “school librarian” to do what thousands of school librarians are doing already under that title. Just as you are protective of your school and faculty, I care deeply about the short and long term of the profession. If the future of school librarianship is not to be a school librarian, then there is no future for our profession.

For a flagship professional publication to put front and center an article (and now editorial) that says school librarians can’t do technology integration effectively as school librarians is frankly insulting to the thousands of school librarians who do this day in and day out. Perhaps if the article had been written in a way to more explicitly explain your decision making, readers (and I can assure you I am not the only one who shares my stance) would have had more insight into what factored into your decision making. However, even in light of your comments, I still fail to understand why you differentiate between “academic technology coordinator” and “school librarian.” And I still disagree with SLJ’s portrayal of this “new model” as work that is original and not happening in most school librarians, much less under the leadership from people who are hired in the role of “school librarian.”

2. I’m now quoting Sarah from Rebecca Miller’s editorial at http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/slj/home/893870-312/undercover_librarian_tech_coordinator_sarah.html.csp:

“There are some significant differences, though. As tech coordinator, she’s considered the expert and is more integrated into her teaching colleagues’ work. “Now it’s easier to get people to trust my opinion on technology, which enables me to do more than I could as a librarian,” she says.”

And the million dollar questions that still are still not answered:

A. Why should any school librarian have to go “undercover” in another job title and role to do the work that Sarah does? Why should any school librarian have to move into another role to utilize their skills? I think the editor of SLJ does not truly understand what school librarians are doing, which is very disheartening.

B. If the qualities of the librarians are valued in your school and were doing the work that Sarah was (I would expect they would be doing what she is now as 21st century librarians), why would Sarah feel that it is easier to get the teachers to trust her opinion on technology, and why does her current role enable her to do her work more effectively than she could in the role of librarian? Why the delineation between the work Sarah does and the work the “school librarians” do? And if the technology and library departments are integrated, why aren’t all staff members sharing the kind of work Sarah does? I would really like to know the answer to these questions because it is more than logical to infer that your “librarians” are doing something entirely different from what Sarah does. For me personally (and many other school librarians) is that what Sarah does in your school is what so many of us do as “school librarians” in our learning communities.

3. For the record, I did not spend an entire day writing the blog post, nor was I criticizing Sarah. This week is my district’s spring break, so no school time was spent working on the post in case you think I have nothing else to do during my workday. I would challenge you to come observe my workday at any time—I typically teach 5-6 of 7 class periods daily, sometimes all 7 periods; most periods we are double booked and our instructional services are maxed out in intensive work with students and teachers. I do not get a lunch period or a planning period like classroom teachers. I put in long hours after work to serve my students. I have plenty of faculty and students who will be more than glad to share with you what I do for them and how it makes a difference for them; there are also librarians who have driven as far as 500 miles away to come observe my library that will testify to my work ethic and the quality of service I provide my students and teachers as our program is considered one of the exemplary library programs in the United States. I think anyone in this profession, including Sarah, will tell you I am one of the most tireless librarians or educators, period. I invite you to read my blog posts and visit our library’s LibGuides pages (http://theunquietlibrary.libguides.com) if you want a true idea of what is going on. In case you have any doubt of what I do on a typical day, my library serves close to 150-200 classes monthly in a school of 1800 students and 100 faculty with only one full time librarian (me), one long term substitute librarian, and no clerical help.

4. I think it is legitimate to call upon SLJ to be inclusive of many types of school libraries when they are running major feature articles about models of librarianship and “our future.” As I have stated here earlier this week, every school does have its challenge–there is no doubt that. However, it is also true that some schools are better positioned to offer their students choices, resources, and learning experiences that others are not because of economic factors as well as the difference in how most public schools are structured and funded vs. private schools. I still believe that a better way to have approached this piece on the “future models” would have included an in-depth exploration of more than one example. Every school culture and its inherent dynamics of power and agency are informed by issues of diversity in terms of race, class, and gender–to ask SLJ and any other professional publication for that matter to be sensitive to that when positing one or more examples as “models” is not unrealistic or unfair.

In closing, I think there is a major disconnect between the views of what school librarians actually do portrayed in the article and now this editorial from Rebecca Miller and the reality of what has been happening for a number of years now. Does the editor of SLJ not actually understand that school librarians DO technology integration already and in the context of instruction? Does she not believe we are able to do this effectively as school librarians? Again, I quote Miller’s editorial:

“As she drives tech innovation across the entire curriculum, her work is skill-centered rather than site-centered, and it’s connection-oriented while staying collection-oriented. It also emphasizes learning outcomes over gadgetry and validates the core work of librarians in meeting educational goals.”

Wow, that sounds an awful lot like what school librarians are doing.

While most of it does happen in the current physical space of our library (we are blessed with a 10,000 square foot facility to accommodate up to 4 classes at a time), I can assure our work is skill, learning processes, and standards driven, NOT “site-driven.”

If you look at Empowering Learners: Guidelines for School Library Programs (http://www.alastore.ala.org/detail.aspx?id=2682), today’s school librarians are integrating learning into classrooms through a diverse range of strategies and in the context of authentic classroom learning. The article fails to actually explain WHY any school librarian should have to go “undercover” or move into another job title to do the exact same work you would already be doing as a school librarian. There is absolutely no reason why any school librarian should not be able to do what Sarah does and in the context of their role as a librarian in their learning communities.

Buffy Hamilton

LikeLike

Very intersting. Speaking of SLJ, the article on “Common Core” I responded to in our listserv:

I am more thinking out loud than posing a question, but I am curious, having just read the latest SLJ article on Common Core Standards.

http://tinyurl.com/7tsst3u

I am trying to get a handle on this from an LMS perspective. The article hints at re-evaluating our collections, to focus on quality non-fiction books and things of that nature. The trouble is, these are the current trends I am finding:

1) Readership is down 25% this year. This number is actually based on my stats of total items checked out from Sept-March. That includes USB’s and so forth (I haven’t gotten deeper into the stats yet, but still, down numbers are down numbers. We had some solid senior readers last year and this year’s freshies do not take their places.

2) Non-fiction is disappearing. I hardly see teacher’s requesting non-fiction books since they do not already. Considering the small budget and the disappearing of print non-fiction books (at this level it seems), how is this feasible?

3) The article mentions purchasing ebooks so students can utilize them at once. Last I checked, an “unlimited usage” book runs a lot of money.

4) The article also mentions increased periodical purchasing. Really?

I suppose a lot of this depends on context, budget, teacher connections and so forth. I’m just curious where everyone else is with this.

Thanks,

Bob

LikeLike

I am a 33 year school librarian and I have taught in a small rural K-12 school, urban elementary schools and am now fortunate to be working in an urban high school of 1,000 students and a staff of over 60 people. While it becomes more difficult to keep up on everything that our students will need,I have always known that professional development is the key. I have a bone deep conviction that when you come in the library you should get what you want, when you want it….even if you don’t know what it is until you share your ideas.

When I entered the profession the discussions were centered around how to make sure that we were recognized as teachers and professionals. It seems to me that we have not moved far from this in 33 years! I have no answers to this new spin on this old problem but I can tell you that we make the solution happen every time we walk through the school doors.

I am disappointed in SLJ’s decision to try to give us yet another name. We have always been the ones who people expect to know about innovations in education and introduce them to our customers. Thank you, Buffy and others, for taking up the fight. My thoughts are with you. Long live school librarians!

Sincerely,

Shelia K. Blume

LikeLike

I can easily understand both sides of this discussion. It has been interesting to follow. Could it be that the roles in a school are not as separate or as clearly different as they were a few years ago? Not only the role of a librarian but many roles in a school? It seems that we all take on roles that utilize our expertise and serve our school communities. I know there are schools where the technology people do the work describe, schools where the librarian does the work, schools where classroom teachers take on that role and schools where coaches take on that role. I think the best thing possible is for administrators like Sarah’s to create opportunities for people and programs to work together and collaborate to create these opportunities for children. There is too much work for one person in a librarian position–to create opportunities to pull library, technology, and classrooms together make sense. i would love to hear more about the collaborative piece because to me, that’s the key to quality librarianship.

LikeLike

I am amazed that a publication that is written for school librarians would be so unaware of what is happening in the profession on a daily basis. We all know what we do..now SLJ will know too…”A rose by any other name…” Librarians do not need new titles to be validated

LikeLike

“Doctors” have been called “doctors” for centuries, even though their methods and technologies have changed greatly. Why can’t that be true of librarians?

LikeLike

In my personal experience the administrators’ desire to be technologically present, along with their misunderstanding and/or lack of knowledge of what we do has led to the technology coordinator vs. librarian situation. I continue to hear announcements by the technology staff of new resources for teachers to try, methods to use for searching, web evaluation, etc. when we’ve been doing these things all along. It is frustrating but I continue to promote my services and strengths as much as possible. Thank you, Buffy, for your insightful remarks.

LikeLike

I agree with embracing what we are…Librarian’s. I have also been given the title of Media Specialist, but when somebody asks I still say Librarian. Just because we are changing the way we teach things and what we might do doesn’t mean we have to change the title. I also agree that we have to evolve with technology and where it takes us, but that doesn’t mean we need to do things that is not part of being a librarian. I have heard of librarian’s doing things that are not in the job description and nothing to do with their degree. Again, we do have to change and evolve, but need to make sure we still are doing what we are supposed to do. I’m trying to embrace the change!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on the KSS Learning Commons.

LikeLike

Fabulous assessment- with feeling, as usual. The unquiet librarian is seldom quiet with regards to sensible inspiration. I currently work with another teacher-librarian in a very busy learning commons style library in a senior (10-12) school of 1800 students. We have had a strong healthy tradition as a library program but like you we both ( yes we are lucky to have 2 TL ) challenged by the times and shifting ground of priorities , policy and decision making. Virtue and value do not seem to be variables today. Rather than being strong practitioners and leaders of learning we are becoming more and more just bookkeepers and administrators of facility. Non-enrolling teachers ( without student rosters) do not get funded in our system so we are seen as a liability. The trend here is becoming change the library to a multipurpose facility with books and reduce librarians – because we have the Internet. Despite being under more demand than ever the stereotypes and ignorance prevails. I worry that good people are still making foolish policy with regards to library services. I have tried to stop fretting and just revolt by doing. Hope for the best.

LikeLike